Introduction

First reported late December 2019 in Wuhan, China, the current number of COVID-19 confirmed individuals has surpassed three million. Several countries have imposed measures to prevent the spread of disease, including public transport, school and workplace closures, public event cancellations, and local or national lockdowns.

The Philippines has also implemented such measures in the form of an “enhanced community quarantine”, with the hopes of flattening the curve to avoid stressing our health system to its full capacity. However, we continue to have a lot of questions, especially as we’re stuck at home. How do these interventions actually help prevent the spread of disease? How much can we flatten the curve? In this article, we hope to simulate interventions including social distancing, lockdown, and mass testing to gain a better understanding of how these interventions work.

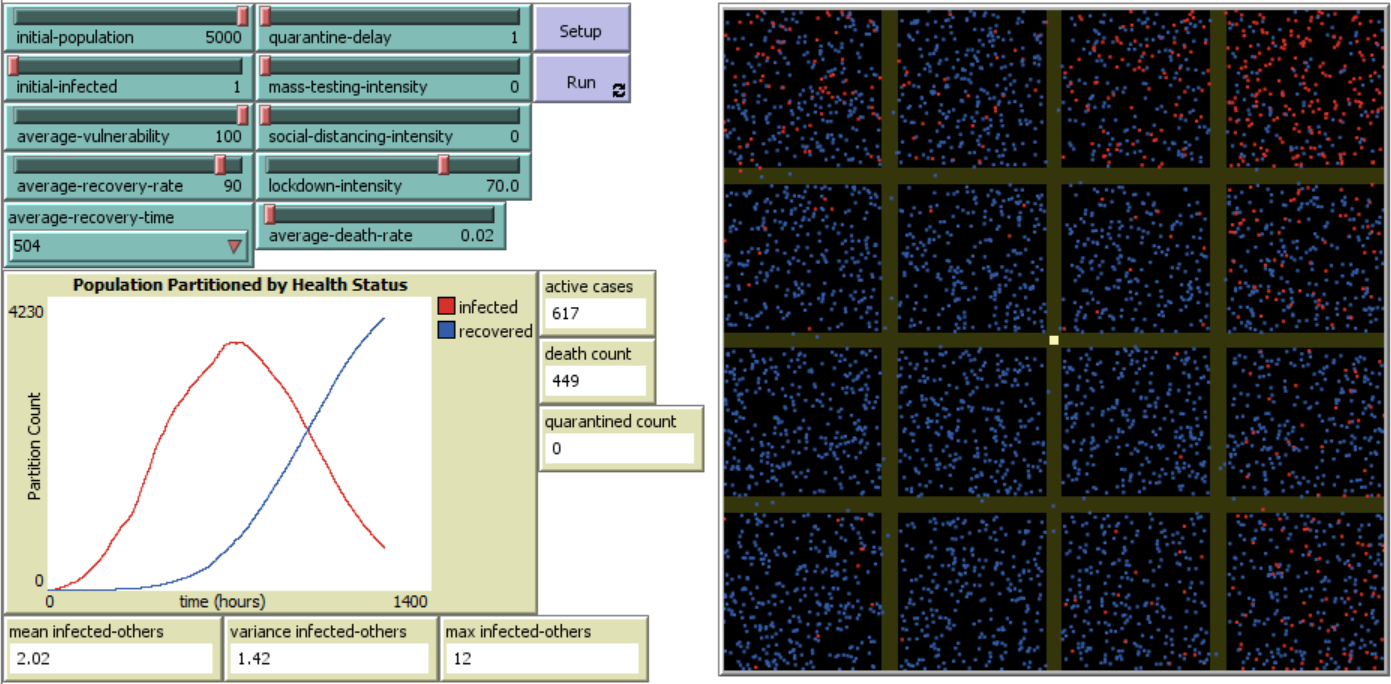

Figure 1. Agent-based modelling in Netlogo.

Figure 1. Agent-based modelling in Netlogo.

Agent-based Modelling and Netlogo

We use agent-based modelling through Netlogo as this allows us to model interactions between agents and simulate different environments. Our agents have randomized movements but we can characterize them by giving properties, such as hygiene. Our environment can be specified as well, such as providing a strict social distancing measure between individuals. Additionally, since implementation of interventions vary throughout different municipalities, we can adjust the intensities of interventions.

Through these simulations, we can observe how agents navigate the pandemic given environment variables of social distancing, lockdown, and mass testing. Consequently, we can observe and quantify the effect of these interactions on recovery and death rates. Figure 1 shows the Netlogo interface, the parameters, a graph of a sample intervention, and the space in which agents are found. Additional details of our model can be found in this Github repository and part I of this article. However, a caveat to this analysis is that it is a simplistic model of the complex COVID-19 pandemic. The agents are random and have random movements, unlike in real life. Although this model cannot provide any predictions, our goal is to compare interventions and identify potential next steps.

Parameters of Interest

One of the first promoted behaviors during this pandemic is social distancing. In our project, we modelled social distancing intensity as the probability of agents to observe the right distance from other agents. The more intense the parameter, the more probable agents are to stay six feet away from each other. For instance, if the setting is set at 20% intensity, only 20% of agents observe social distancing.

Another intervention undertaken during this pandemic is a lockdown. We designed the lockdown intensity parameter in this project as the probability of an agent to cross a border successfully. This parameter attempts to model agents’ behavior of crossing between boundaries, such as cities or provinces. Since agents move around randomly, this parameter is only activated once an agent attempts to traverse a border (defined as green lines). The more intense the parameter, the less likely an agent is to cross borders. For instance, if the setting is at 20% intensity, agents who try to pass a border are likely to succeed 20% of the time.

We modelled mass testing intensity as the probability of an agent to get randomly tested every 24 hours. The more intense the parameter, the more likely an agent is tested within 24 hours. An important note is that this is different from the targeted testing of suspected or probable individuals since these individuals have already been isolated and monitored. This parameter captures random testing of freely moving agents. Additionally, since testing did not necessarily imply immediate isolation, we identified another intervention that was linked to mass testing: quarantine delay. We defined quarantine delay as the number of days quarantine or isolation is delayed after being tested positive.

Lastly, although this is not an intervention that is implemented by an external body, we also measured agent vulnerability. Agent vulnerability is a characteristic that we gave to an agent to describe their hygiene in terms of wearing masks or washing their hands. The assumption for this parameter is that the more hygienic an agent is (lower vulnerability), the less likely they are to be infected when interacting with infected agents.

Findings

After playing around with the model, a few insights are apparent. First, it may be necessary to do random mass testing outside of the usual symptomatic monitoring and contact tracing. Second, partial lockdowns always result in multiple peaks of infection

Physical hygiene matters

Our model has two parameters that are closely linked to individual physical hygiene: social (or physical) distancing and agent vulnerability (hygiene). Our simulations revealed that both are necessary interventions to prevent the spread of infection. The graph reveals that with social distancing alone, the curve is flatter compared to other interventions. Thus, it appears that we, as individuals responsible for our own hygiene and behavior, are the frontliners in preventing the spread of COVID-19.

This appears to be true even in the real world scenario. Sweden already reports a plateau in their infection and fatality rates. The government’s strategy was met with outrage from the international community, considering how lax. They asked their citizens to be responsible and observe proper social distancing, which now resulted in stabilized numbers. However, we must add a caveat for this scenario. It might be possible for Sweden but it could be irresponsible and inhumane to ask the same for the Philippines, with our denser homes and a weaker health system.

Partial Lockdowns Result in Multiple Peaks of Infection

Lockdowns are expensive and disruptive interventions, causing plunging markets, layoffs, closed businesses, and even negative oil prices. It is no surprise that we all want to go back to normal life. But what happens when a lockdown is lifted? Germany has reported that their infection rates suddenly increased after easing their lockdown. Additionally, there are reports of a second wave of infection in some countries of Asia.

In our simulations, we found that partial lockdowns indeed result in multiple peaks of infection. This happens because agents are able to roam from one area to another. When an infection is present in one area, an agent can bring the infection to another area. This results in another surge of infections coming from that newly infected area.

One example is comparing the curve of NCR and Region 7. When taken as a whole, it appears that the Philippines is at its second peak of infection. However, a closer look into NCR and Region 7 numbers will reveal that the first peak comes from NCR and neighboring provinces while the second comes from Region 7. There is merely a lag in the peak of certain regions due to the delay of transmission from partial lockdowns. Lockdowns appear to be helpful in flattening the curve. However, lockdowns must be lifted with a lot of data and the necessary precautions. One of the most important may be strengthening health system capacity in areas near highly infected regions so they are able to handle potential localized peaks of infection.

Data Source: DOH Data Drop

Another example is from one of the simulations we made with our agents. Different groups of healthy agents are divided by these yellow boxes on different areas but since in this simulation, this is only a partial lockdown, even a single agent can spread the infection to the neighboring agents.

Mass testing + immediate isolation

Since mass testing is quite expensive to implement for whole populations, we look into varied intensities of random testing. Improved testing of agents slows down the increase in infected individuals compared to when no intervention is present.

However, immediate isolation of positive individuals works better than random testing alone.

The graph below compares mass testing intensity at 20% (20% of agents are randomly tested) when quarantine delay is at one, three, and seven days. Just visually from the graph below, improved isolation from three days to one day reduced the peak of infected individuals in our simulation.

Conclusion

Our simulations revealed that certain measures may be necessary to flatten the curve. Among these are government efforts of increased random testing in communities and strategic lifting of community quarantines or lockdowns. Nonetheless, one important finding is directed towards our own behaviors during this time. It appears that individual behavior matters a lot in preventing the spread of COVID-19. We applaud our frontliners who have been working for almost two months now but we, ourselves, have our own responsibilities to prevent the further spread of disease. Thus, if we can, we must practice physical distancing and good hygiene.